Offering a prize is one way to attract a lot of publicity. Unfortunately not all prizes are created equal.

Let's compare the prizes offered by Kent Hovind (aka 'Dr Dino'), a creationist, who is currently offering

$250,000 for scientific evidence of evolution with the prize offered by James Randi (aka 'The Amazing Randi') who has

one million dollars to anyone who can prove they have 'supernatural powers.

The first one sounds easier doesn't it? But like all offers you need to read the small print. To satisfy Hovind you would have to show, and I quote:

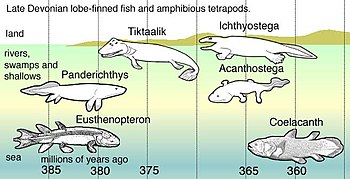

* NOTE: When I use the word evolution, I am not referring to the minor variations found in all of the various life forms (microevolution). I am referring to the general theory of evolution which believes these five major events took place without God: 1. Time, space, and matter came into existence by themselves. 2. Planets and stars formed from space dust. 3. Matter created life by itself. 4. Early life-forms learned to reproduce themselves. 5. Major changes occurred between these diverse life forms (i.e., fish changed to amphibians, amphibians changed to reptiles, and reptiles changed to birds or mammals).Wow. That suddenly got a lot harder. In fact it can now be argued that to satisfy Hovind you would need to prove not only that God didn't do the aforementioned five acts but that he couldn't have done so. This would imply that God is not omnipotent, so satisfying Hovind may involve proving that God does not exist. Christian theists have already pointed out that the only way to truly know whether God exists or not is to be omniscient - that is to be God yourself!

Enough. This is clearly just a publicity stunt. If you do want to read more you can find a

nice summary and links at the talkorigins site. Bottom line, if you want to play in the Science sandbox you need to play by the rules.

The

offer by James Randi is actually far more interesting. In order to get Randi's million bucks all you need to do is show a single convincing case of a supernatural power (

eg. Dowsing. ESP. Precognition. Remote Viewing. Communicating with the Dead . Homeopathy. Faith Healing. Astrology. Prophecy. Levitation. Reflexology. Clairvoyance. Graphology. Numerology. Palmistry. Phrenology.) What is a convincing case? One that is clearly shown cannot be a trick.

The interesting bit to me is in the

correspondence between the James Randi Educational Foundation and the claimants as they try to agree on a testing protocol (look at the ones with the most replies for the most interesting debate). This has a lot of relevance to today's discussion on putting your hypotheses to rigorous tests. Psychics

may be able to read your mind but they may also be able to read your body language or just plain cheat. If you give them easy tests then passing them doesn't really reveal very much. A

good test is one that can distinguish real psychic powers from cheating. I admire Randi for putting his money on the line in this way. Not only is he inviting believers in the paranormal to put themselves to the test but he is also saying that he does not believe he can be tricked. It probably helps that Randi was a magician himself and is, I imagine, hard to fool.

Labels: Scientific Method

I'm convinced that it is getting harder and harder to tell stories in The Onion from real stories. The US has long maintained that there is no Mad Cow disease in the US. Critics had argued that the level of testing was far too low to actually detect it if it was present. Eventually the Agriculture department increased the testing rate - and lo and behold they discovered infected cows (you probably read about this in the press because other countries now banned US beef).

I'm convinced that it is getting harder and harder to tell stories in The Onion from real stories. The US has long maintained that there is no Mad Cow disease in the US. Critics had argued that the level of testing was far too low to actually detect it if it was present. Eventually the Agriculture department increased the testing rate - and lo and behold they discovered infected cows (you probably read about this in the press because other countries now banned US beef).